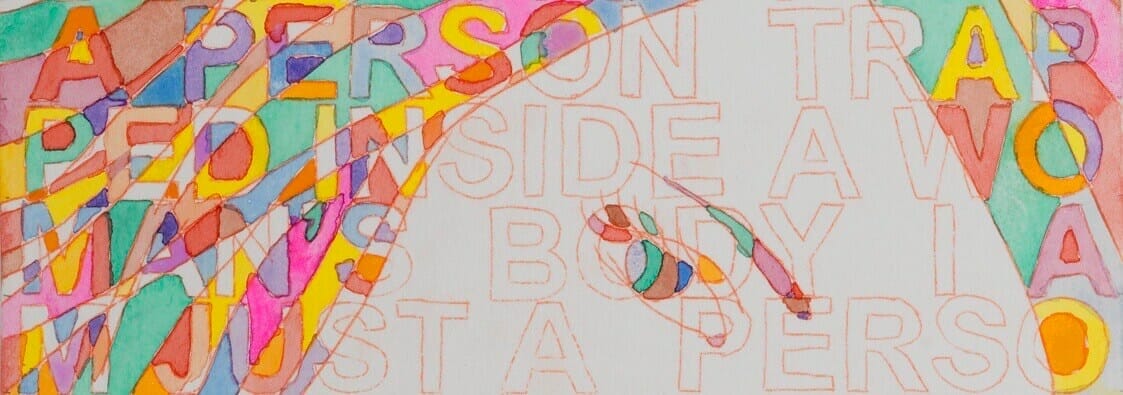

In Portrait #1 (2013), the woman’s face emerges through the mantra “I am just a person trapped inside a woman’s body.” The portrait is composed of both thinly drawn lines that outline the subject as well as letters which are superimposed onto the face. Portrait #1 is the first superimposition of text and figures in Amer’s portraits. In fact, the series Portraits of the Women that I Know began in 2013 with this portrait and all subsequent works in that series show Amer’s development of this technique.

The subject of this portrait has been represented frequently in Amer’s paintings: she is one of the many characters from the pronographic magazines that Amer has painted throughout her artistic trajectory. While in earlier paintings, the female characters were painted in rows and repetitions, with portraiture, Amer is asserting the character’s personhood. The mantra becomes part of the woman’s face and hair as the letters are part and parcel of the different elements of the portrait. In Portrait #1 the superimposition technique gains a particular significance because of the meaning of the slogan itself.

Feeling Trapped by Identity

“I am just a person trapped in a woman’s body” says the subject in the portrait. Latent in this enunciation is the realisation that “person” and “woman” are not synonymous. All the more, being “just a person” supersedes being a woman, and their forced correspondence makes a person feel trapped or mis-represented. The mantra problematizes the fact that identity is fixed and assigned. In this enunciation lies an act of disidentification, of becoming “just a person.”

The problem of identification is a recurrent theme of Jacques Rancière’s work. For the contemporary French philosopher, identification is the forced assignment of titles or roles, whereby the roles falsely claim to fully render visible the people but in fact only serve to fix them to these very roles. This process of identification is defined as “the allocation of ways of doing, ways of being, and ways saying, and sees that those bodies are assigned by name to a particular place and task.” (Disagreement, 1998). For Rancière, the process of identification, which he dubs the police order, is what fixes the “person” to the role of “woman.”

Superimposition Tackles Identification

How would Rancière account for the mantra in Portrait #1? The mantra points to the undoing of the “natural” association between the person in the portrait and her classification or status as a woman. For Rancière, this undoing involves the subject moving beyond the limits and allocations given by the fixed identity. What occurs is a deregulation or a challenge set to that police order. This produces a reconfiguration whereby we come to understand that identities are not fixed, that “person” and “woman” are not co-exchangeable.

Here, Amer’s painting technique is in dialogue with Rancière. Indeed, her superimposition technique highlights a visual disturbance whereby neither can the face be distinguished properly nor can the mantra be read clearly. This is not a purely figurative portrait. The resulting visual distortion manifests the gap between “person” and “woman”. Portrait #1 is a challenge to both figuration and identification. This reconfiguration is transferred onto the viewer as a challenge to the society perpetuating such modes of identification. Amer pushes us to ask whether assigned roles are truly representative.

There is no natural or fixed correspondence between being a person and having a woman’s body. The portrait, the distortion it produces in terms of aesthetic experience, highlights the dissociation present in the slogan. That dissociation is Rancière’s subjectification. That reconfiguration is Amer’s superimposition.