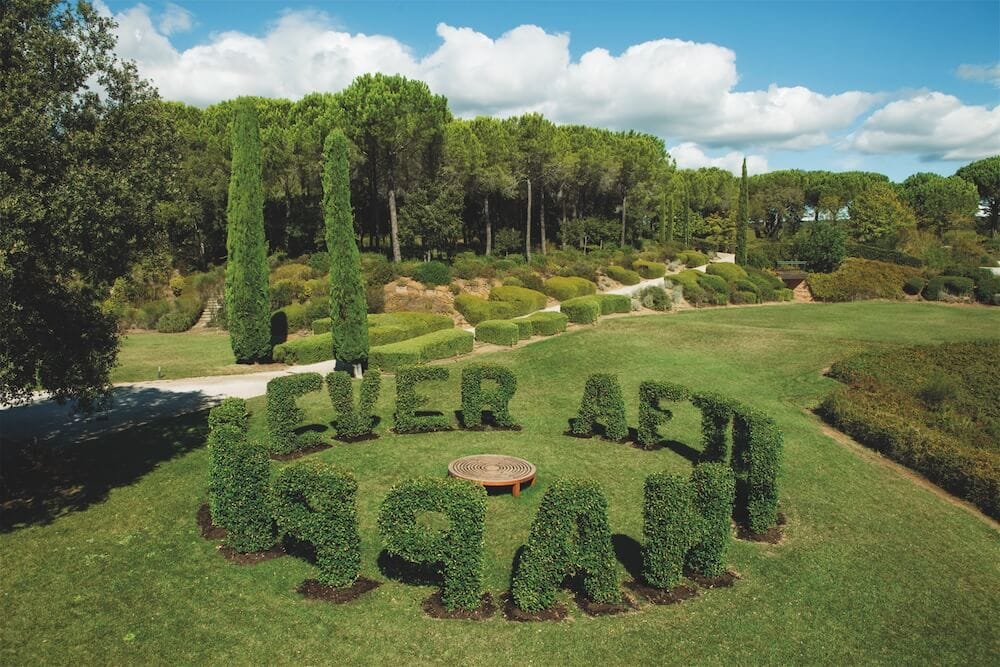

Ghada Amer’s garden installation titled Happily Ever After is a circle of rose bushes and jasmine flowers spelling out the notorious final three words of fairy tales’ ending: “And they lived happily ever after.” At the heart of the five-foot stainless steel structure lies a round bench on which visitors are invited to rest and from which they only have a view of a few letters or a word at a time. Interestingly, while this garden was recreated in multiple locations, first at the Queens Museum of Art in New York and at Sudeley Castle in Withycombe (Gloucestershire, England) in 2005, there is today and since 2009 only one permanently displayed Happily Ever After garden in Tuscany, Italy, at the vineyard of Tenuta dell’Ornellaia.

Happily Ever After: the beginning of a tale

Fairy tales inspire and provoke reflection and criticism. At the centre of feminist debates, their contemporary adaptations often attempt to reinvent the familiar stories to suit social ideals. From this perspective, Amer’s garden can be considered an adaptation of fairy tales. Indeed, by creating an endless loop that replays the last line of these stories, the garden physically becomes a narrative space, delineated by the circle. When visitors enter the garden, they step inside a story and for the entire time they remain in it.

Narrative space can be understood as the broad socio-cultural context in which a story is set, the more specific location in which actions unfold, or – and this is the definition of interest here – as the world which is completed by the reader’s imagination (see Marie-Laure Ryan). In Amer’s garden, a visitor’s presence inside the physical space demarcated by those three words (happily ever after), propels him/her to imagine the story s/he occupies. This is rendered possible through anyone’s knowledge of a fairy tale’s structure; visitors of the garden can easily immerse themselves inside a story of their own imaginings. Each individual becomes enthralled by her/his own inventions, carried away in wonder by the dreamlike world fairytales create. Happily Ever After is a narrative space where visitors can suspend their disbelief.

Happily Ever After: a hopeful ending?

Even more, thus engulfed in a fairy tale, visitors not only create but equally participate in the narrative. In other words, they become characters by virtue of their physical presence in the narrative space of the garden. And this transports them to an important characteristic of the fairy tale: a happy ending that inspires hope in the face of injustice (Warner, xxiii). Here, Ghada Amer’s installation could allude to the injustice that percolates many traditional fairy tales: gendered stereotypes. The promise of a better future, one where good prevails, reigns over the garden.

But the tale must eventually come to an end in the same way that Amer’s various installations cease to exist. All but one, the garden in Italy, which must be constantly maintained and looked after in order to remain pristine and blossoming. This is not unlike the fight for love or equality which demands continuous efforts.

To live happily ever after, one must endeavour to look after the beloved, nourish the relationship and grow in intimacy, much like gardeners must toil the garden and trim the shrubs to keep them growing. Able to experience the tale’s finale, visitors-characters are invited to recognise the ephemeral nature of fairy tales and ponder the fragility of their happy ending. Happily Ever After reshapes fairy tales according to its visitors’ imagined narratives. In it, we are invited to live happily ever after, if only for a moment.

Works cited:

- Warner, Marina. Once Upon A Time: A Short History of Fairy Tales (Oxford: Oxford

- University Press, 2014).Ryan, Marie-Laure. “Space, in Handbook of Narratology, edited by Peter Hühn et. al. (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2009).