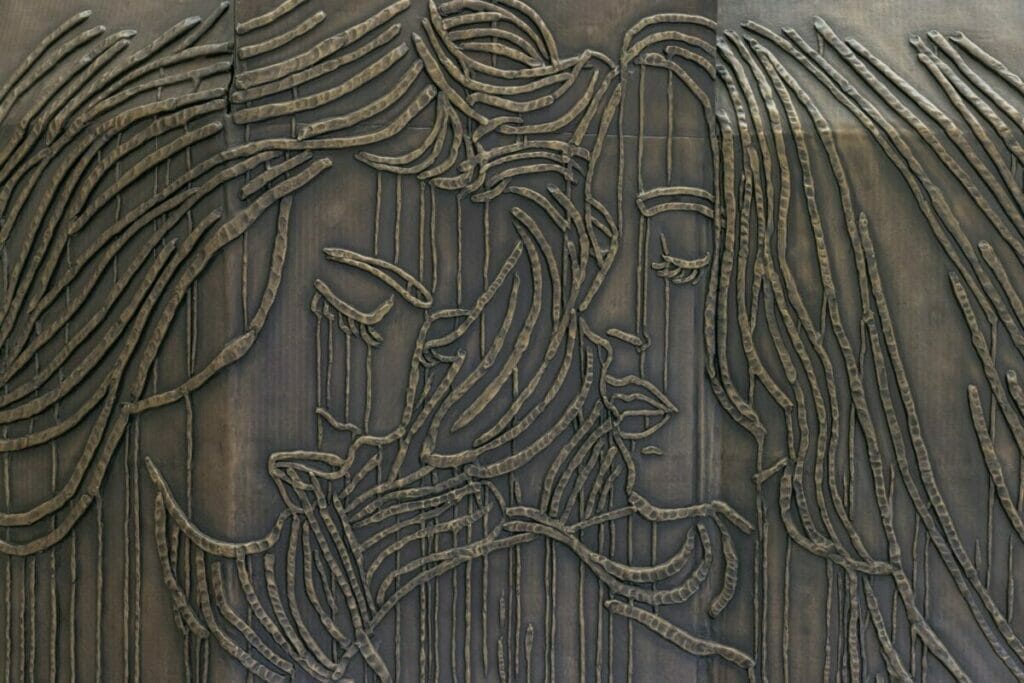

Larger than life, the women on Ghada Amer’s paravents emerge from bronze panels in raised lines that give a tactile element to each piece. On one side of a paravent, a woman sculpted out of bronze ridges has hair cascading around her shoulders, as if to create a peekaboo partition between her skin and the viewer’s sight line. Shrugging her shoulder lightly, she plays with her strap as she looks over her shoulder, eyes downcast, a slight smile hovering on her lips, seemingly prepared to disrobe. On the other side of the paravent, two women seem to have just brushed their tresses to the side as they move closer together, one reaching out a hand to help the other shed her underthings.

Watching women dress or undress in art is a theme as old as time, from the biblical Susanna and the Elders in Renaissance paintings, to Ingres’ odalisques or Bonnard’s women in bathtubs. However, watching these scenes of undress unfold on giant paravents – objects intended to create privacy or, depending on the context, a sense of sensuous mystery, as a woman slips into something more comfortable – is another thing altogether. After all, if we can clearly see the women undressing, isn’t this visibility ruining the mystery, by showing openly what usually happens behind the partition right there, on the screen?

Ghada Amer’s “paravent girls,” if we can call them as such, are the newest addition to the artist’s pantheon of female subjects who challenge the viewer’s gaze. In this latest series, Ghada Amer has chosen to use paravents, or folding screens, as her creative canvas. As a free-standing, adjustable object, the paravent is also a movable partition that can be unfolded to erect a barrier or create a private space. And yet, Ghada Amer’s screens do not fold. By casting them in a permanently unfolded shape, the artist repurposes the paravent to literally screen images of women’s bodies on an object often used to screen those same bodies from view.

Can Ghada’s girls be seen as protectors, and her bronze screens, armor? After all, the physical form and function of Ghada Amer’s paravents contradicts the traditional use of this object as a foldable, movable piece of furniture. Ghada Amer’s screens are heavy objects created out of cast bronze and cannot be folded or easily moved around. If the choice of material seems to eliminate the mere possibility that these paravents would be used for practical purposes, this is reinforced by the fact that the screens are also bolted to the ground when they are installed–immovable, the solid bronze screens provide a more permanent and protective barrier.

The folding screen, beyond its practical and decorative functions, has also long served as a sexual symbol in opera, theatre, cinema, and the arts. The screen’s ability to conceal, or reveal only outlines, makes it a tool and foil for flirtation and seduction. However, by creating paravents out of bronze, as opposed to canvas or other semi-transparent or transportable materials, Ghada Amer’s screens can truly protect a user’s privacy, as no light can get through the bronze and light up a silhouette behind the screen. If you were to stand behind one of these screens, no one would be able to see you. Instead; the only figures that are visible are the ones Ghada Amer has deliberately chosen to sculpt on her folding screens.

What then, is behind the scenes – or rather, behind the screens? Historically, many paravents would feature a highly decorated outward-facing illustration on one side, and a simpler motif on the “private” side of the screen. Ghada Amer, however, spent time creating art on both sides of her folding screens, giving equal weight to what a person on the front-facing side of the screen and the person behind the screen might see. By sculpting equally detailed figures on both sides of her screens, she establishes her paravent as a freestanding sculpture designed to be viewed from all sides, with no hidden or unfinished side.

The method Ghada Amer uses to bond her figures to the background bolsters their visibility. When creating the images of the girls on her paravents, the artist did not carve them into the bronze, but rather, she created them relief, raising them above the bronze background. By raising the figures on the bronze panels as opposed to engraving them into the surface, Ghada Amer continues her practice of putting the female figures first, layering the raised bronze lines on the bronze panels like she stitches figures onto painted canvases in earlier works. But where Ghada Amer’s embroidered figures are frequently obstructed by hanging threads on her painted canvases, the raised figures on the folding screens remain visible through the drips that seem to streak down the paravent. By clearly sculpting images of female eroticism onto an object that has long been used to arouse or create mystery, Ghada Amer breaks down the power of an object designed to conceal.

Herein lies Ghada Amer’s paravent paradox. Hidden from view while gazing at the bodies, the screens protect the viewer’s privacy but also enable the consumption of sensuous imagery. That this consumption takes place in a gallery setting, where exhibition is the purpose of the space, draws attention to both the exhibitionism of the bodies on the screen but also the viewer consuming these images. The protection that the paravent is supposed to provide for a private viewing of sexual bodies is complicated by the protected-yet-public experience of viewing the paravents in a public space.